By TJ Martinell, The Center Square

One argument made by boosters of House Bill 1054 restricting law enforcement’s ability to vehicularly pursue suspects is that it would reduce the number of fatalities caused by those police chases.

A state traffic data analyst says these fatalities represent a statistically insignificant percentage of total traffic deaths, which are at a 30-year high. At the same time, she argues the existing data is too incomplete to draw significant conclusions as to the effects of the 2021 state law regarding overall vehicle fatalities.

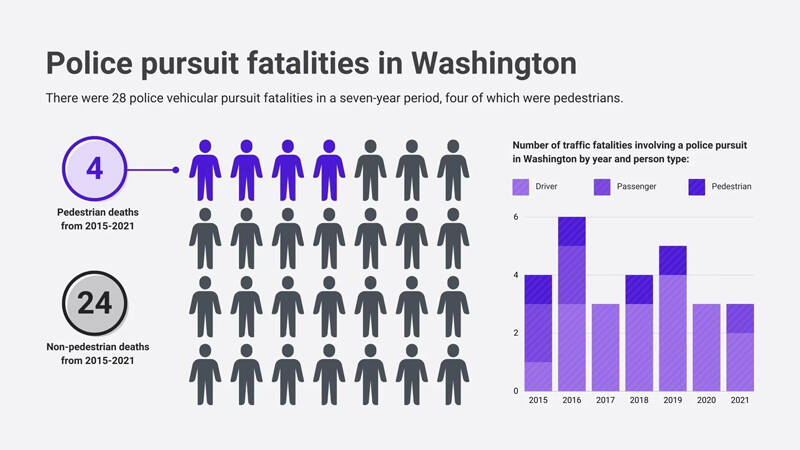

Data from the Washington State Traffic Safety Commission, or WSTSC, shows that in the seven-year period from 2015-2021, there were 28 police vehicle chase deaths. The deaths are categorized into “driver,” “passenger,” and “pedestrian.” In 2020, there were only three fatalities resulting from a police vehicle chase. Of those 28 killed in the seven-year period, 19 were drivers, and only four were pedestrians.

Meanwhile, last year alone there were roughly 750 total traffic fatalities – the most since 1990 and an increase from 2021 of 80 fatalities. In 2021, there were three police vehicle-related fatalities, or .04 % of the 670 total traffic fatalities.

“We are in a traffic safety crisis,” WSTSC Research Director Staci Hoff told The Center Square. “Police pursuits are really stealing the show. Police pursuits are not a huge fatal crash factor in our world [traffic data collection].”

The merit of restricting most vehicular pursuits has gained increasing opposition since 2021 due in part to what critics argue is increased crime and vehicle fatalities caused by criminals when police don’t pursue. Recently, a driver clocked by local police driving at more than 100 miles per hour went unpursued and later crashed, killing two children. This month, a suspect driving a vehicle in a Spokane parking lot hit a pedestrian and fled without pursuit. The pursuit of a suspected drunk driver in Spokane County was called off and only reengaged after local law enforcement was notified by Idaho police that the suspect was wanted for aggravated assault against one of their officers, an offense that under HB 1054 still permits vehicular pursuit.

Law enforcement groups such as the Association of Washington Sheriffs and Police Chiefs, or WASPC, argue that there’s enough data currently available to justify rolling back restrictions on police vehicle pursuits. According to WASPC, the number of drivers fleeing Washington State Patrol officers more than doubled, from 2021 to 2022.

WASPC Executive Director Steve Strachan told The Center Square that “any traffic death is a tragedy, but I think the analysis of public policy should really start at the significantly increasing number of traffic deaths statewide. All the analysis that we’ve been looking at with changing the pursuit law does not look at the downstream effects. I don’t think that anyone is able to draw a straight line from the change in law to increased traffic deaths. What I can say we’ve certainly had significantly more people driving away [from police].”

He added that “to look at the differences in in the increased number of traffic deaths – without question it has at least some relationship to the unintended consequences of state law changes. I don’t think it’s the only factor.”

While advocates for police pursuit reform point to studies that have been called into question, Hoff said that there is a lot of nuance involved when interpreting data on police pursuit deaths.

“[People] say that potentially fatalities involving police pursuits have gone down,” she said. “But we don’t know if they’ve gone up. They’re not pursuing, and we don’t have that data at all if someone is killed when the police don’t pursue. The data is so incomplete that it can’t really fully tell the story on either side of its debate.”

One problem with interpreting the data is defining “pedestrian.”

For example, if a motorcyclist is pursued by police, drops his bike, and is struck by another vehicle while standing it back up, he’s considered a pedestrian fatality rather than a driver fatality.

“It’s all about the un-stabilizing event that led to the death,” she said, adding that in many of these instances of police vehicle chase deaths, “It’s not even what people are thinking [occurred].”

It’s unclear to what extent legislators sought data from WSTSC during the 2021 legislative session when crafting, amending, debating, and ultimately passing HB 1054. A public records request found that no emails were sent to or front any legislator or their staff to any WSTSC member between May 2020-April 2021.

Hoff said the commission publishes traffic data dashboards on their website for use by interested lawmakers for incidents such motorcycle lane-splitting. Yet, she added the commission does not post a dashboard for police vehicle chase deaths “because there’s so few.”

While the commission doesn’t take a position on public policy proposals, Hoff suggested the state should create a data collection and storage process for police vehicle chase deaths like that already created for tracking use of force incidents.

“That is exactly how they should fix this [data] problem,” she said.

It’s an idea Strachan also favors. “To start to get more specific in what those data points are, makes sense. It’s an area that’s important in terms of making sure we have good public policy.”