By Tim Clouser | The Center Square

(The Center Square) – Hikers have more to watch out for than bears this summer.

Washington state’s gray wolf population has increased over the last 15 years, said Julie Smith, endangered species recovery section manager for the Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife, during Wednesday’s episode of “The Impact” on TVW.

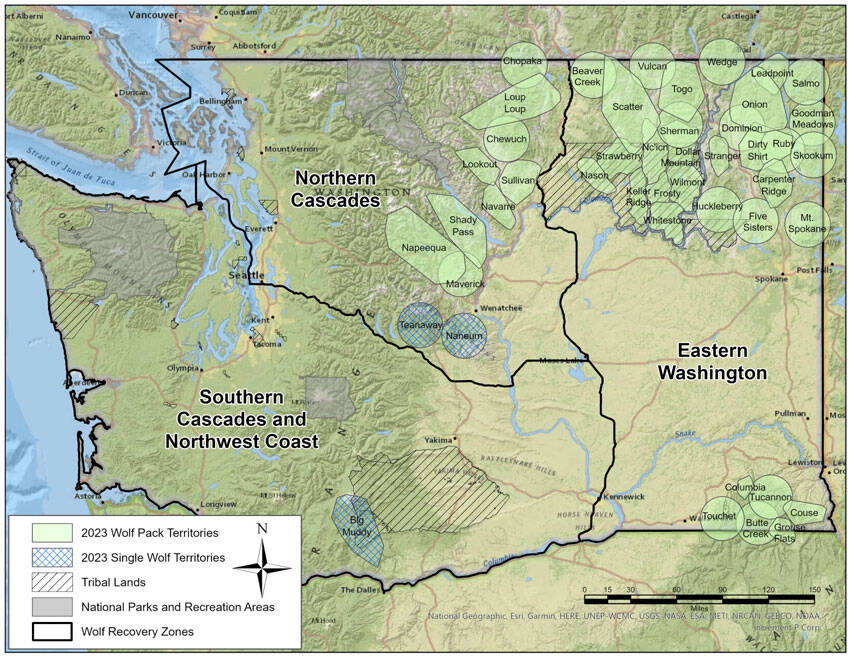

In fact, the gray wolf population jumped by 20% alone in 2023, she said, with packs now moving south of Interstate 90 and further into the western half of the state.

At the end of 2023, WDFW and tribes around the state counted 260 wolves and 42 packs, according to the department’s website.

“Where we expect to see growth is in southwest Washington, where we have a lot of good forested habitat,” Smith said. “We have Mt. St. Helens National Monument; we have Mt. Rainier National Park; those have yet to see their first wolves cross within those boundaries, although they’ve come close.”

Gray wolves are federally listed as endangered. On Tuesday, the U.S. House of Representatives passed House Resolution 764, the Trust the Science Act, to delist the gray wolf from the Endangered Species Act. The bill isn’t expected to move forward now in the Democratic-controlled Senate.

While previously thought to have been eradicated in Washington for almost 100 years, scattered reports over the decades indicated that some gray wolves made their way over from neighboring states and British Columbia, Canada, according to WDFW’s website.

While this week’s decision moves to potentially delist gray wolves nationwide, the species was federally delisted for much of eastern Washington in 2022. However, since state government still lists the species, it’s illegal to “kill, harm, or harass them.”

Smith said WDFW anticipates the species will continue working its way along the Cascade mountain range and around the Olympic Peninsula. The agency expects population trends to slow as gray wolves occupy more of the state’s habitat.

“[Our wolf populations] don’t tend to just move across and show up in a completely new area of the state where there aren’t any wolves,” she said. “Typically, you’re going to see buds off current packs.”

Given wolves’ ability to adapt, persevere and disperse, Smith said it’s reasonable to assume that western Washington will have strong packs in the next 10 years.

“We manage for recovery in this state,” she said, “… we expect their populations to grow.”

Smith said people can undoubtedly expect wolves in the northeast and southeast portions of the state, as those areas have had established packs for over a decade. There are also increased reports in the central and north Cascades.

Given the shy nature of the species, it’s unlikely for people to stumble upon a gray wolf. Instead, she said that people should expect to see signs, such as scat or tracks. However, she recommended leaving the area cautiously upon spotting a gray wolf.

“The best thing you can do is keep your eye contact with that wolf and slowly back away,” Smith said.

Corrections and Clarifications

This story has been edited since initial publication to correctly reflect that House Resolution 764 to delist the gray wolf from the Endangered Species Act has passed only the U.S. House. It has not passed the Senate.